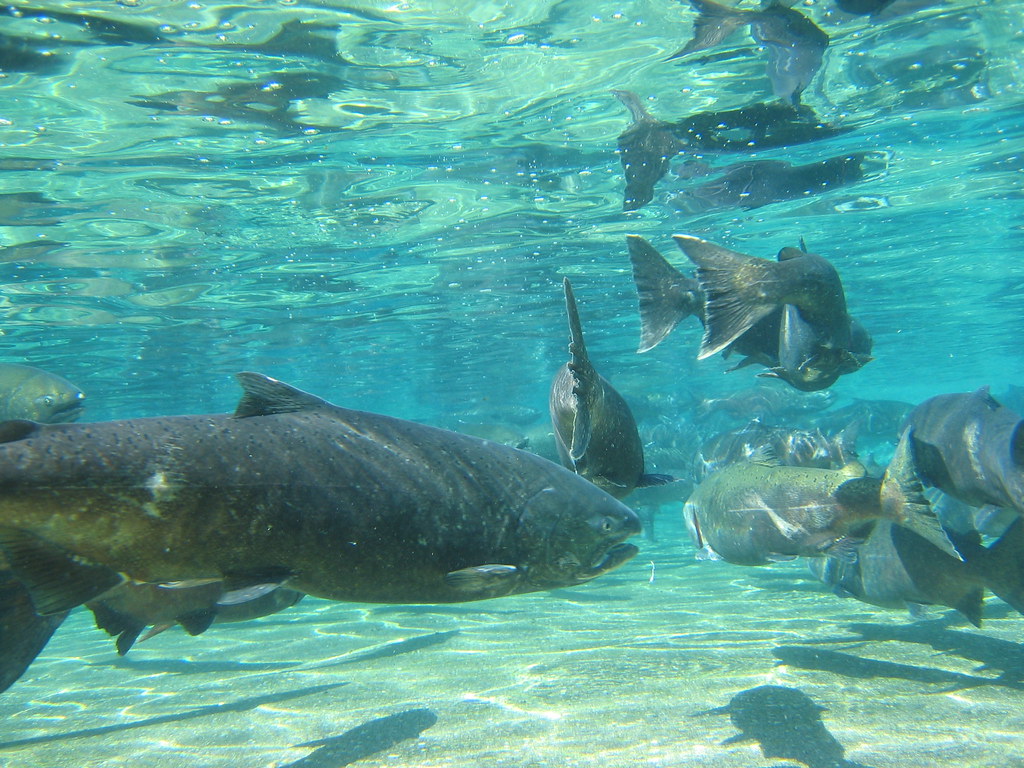

The San Joaquin River Restoration Program celebrated an extraordinary milestone in 2025 when 448 adult spring-run Chinook salmon returned to spawn.

This marked the highest number since the program began reintroducing juvenile salmon back in 2014.

The previous record of just 93 adult salmon, set in 2021, was nearly quintupled by this year’s remarkable return.

For a river that once ran completely dry for decades, these numbers represent nothing short of a conservation miracle.

A River That Forgot How to Flow

The Golden Years

The story of the San Joaquin River’s salmon begins with loss.

Before the 1940s, this mighty waterway supported one of California’s most productive fisheries.

Hundreds of thousands of Chinook salmon made their annual journey upstream, traveling as far as Mammoth Pool at about 1,000 meters elevation, roughly 50 miles above where Friant Dam stands today.

The river teemed with life, supporting both spring-run and fall-run Chinook salmon populations that fed communities and sustained ecosystems throughout Central California.

When the Water Stopped

Then everything changed.

Friant Dam was completed in 1942, standing 320 feet high across the San Joaquin River.

The massive structure provided flood protection and water storage for irrigation in the San Joaquin River Basin.

But here’s the catch: unlike most federal water projects, the Friant Division diverted nearly all of the river’s flow away from its natural channel.

Water that once nourished salmon runs was redirected into canals like the Madera and Friant-Kern canals to irrigate farmland from north of Fresno to Bakersfield.

A Silent River

By the late 1940s, approximately 60 miles of the San Joaquin River had dried up completely.

The riverbed sat barren most years, except during major floods.

Without flowing water, salmon could no longer reach their historic spawning grounds.

The fish were cut off from their ancestral habitat, and by 1949, the spring-run Chinook salmon population had been completely eliminated from the upper San Joaquin River.

The last substantial run of more than 1,900 fish occurred in 1948.

The Battle to Bring Back the River

Taking It to Court

For decades, the San Joaquin River remained essentially lifeless in its upper reaches.

Agricultural interests thrived with the diverted water, while the river itself became an environmental casualty.

That’s why a coalition of environmental groups decided to take action.

In 1988, the Natural Resources Defense Council and fishing groups sued the Bureau of Reclamation, arguing that Friant Dam violated California Fish and Game code because it failed to maintain enough water in the river to keep fish populations in good condition.

The Historic Settlement

The lawsuit dragged on for 18 years, with mounting legal fees and uncertainty for all parties involved.

Finally, on September 13, 2006, a historic settlement was reached.

The agreement brought together unlikely partners: environmental groups led by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Friant Water Users Authority representing agricultural interests, and the U.S. Departments of Interior and Commerce.

A federal court approved the settlement on October 23, 2006, and Congress passed the San Joaquin River Restoration Settlement Act in March 2009.

A Delicate Balance

The settlement established two ambitious goals.

First, restore and maintain fish populations in good condition in the San Joaquin River below Friant Dam, including naturally reproducing and self-sustaining populations of salmon.

Second, reduce or avoid negative water supply impacts to the Friant Division contractors who depended on that water for irrigation.

It was a delicate balance between environmental restoration and economic reality.

Under the agreement, specific water releases from Friant Dam were required to meet the life cycle needs of spring-run and fall-run Chinook salmon.

The release schedule varies by year type: approximately 247,000 acre-feet in dry years and about 555,000 acre-feet in wet years.

As a long-term annual average, Friant contractors agreed to give up approximately 18 percent of their water supply.

You’re better off understanding this as one of California’s most significant water compromises, where farms and fish would have to learn to share a precious resource.

Why Spring-Run Chinook Are Special

A Different Kind of Salmon

Spring-run Chinook salmon face unique survival challenges that make their restoration particularly difficult.

Unlike fall-run Chinook that enter rivers in autumn and spawn immediately, spring-run fish arrive when water temperatures are still cool from spring snowmelt.

They migrate upstream early, then must survive the blazing heat of a California summer before spawning in the fall.

The Cold Water Problem

That’s why these fish desperately need access to cold, clean water in mountain headwaters.

In their historic range, spring-run Chinook would “oversummer” in cool tributary streams, waiting out the hot months before spawning began.

But with most cold-water habitat now blocked by dams, spring-run Chinook can survive in only a few places in the entire Southern Sierra watershed.

Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1999.

Genetic Lifelines

Today, some populations still exist in Sacramento River tributaries like Deer Creek, Mill Creek, and Butte Creek.

These remnant populations became the genetic foundation for San Joaquin River restoration efforts.

Fisheries biologists collected salmon from these surviving populations to increase genetic diversity and create a new population uniquely adapted to San Joaquin River conditions.

The Long Road Back

Building a Team

Bringing salmon back to a river that had been dry for 60 years required creative solutions.

The San Joaquin River Restoration Program became a multi-agency collaboration involving the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Reclamation, National Marine Fisheries Service, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, and California Department of Water Resources.

Together, they worked to restore flows and reintroduce salmon to a 150-mile stretch of river from Friant Dam to the confluence with the Merced River.

The First Fish

Starting in 2014, the program began releasing juvenile spring-run Chinook salmon into the restored river reaches.

These young fish, raised from the remnant Sacramento River populations, were marked and tracked as they made their way downstream toward the Pacific Ocean.

In 2025 alone, approximately 200,000 marked juvenile salmon were released into the restoration area.

The hope was that some would survive the dangerous journey through predator-filled waters, reach the ocean, mature, and then find their way back home.

Still a Broken River

But here’s the deal: even with water flowing again, the San Joaquin River remains heavily altered by human development.

The river system now includes 27 dams, six reservoirs, and nine hydropower plants along its 366 miles, making it among California’s most heavily dammed waterways.

Multiple in-stream structures prevent salmon from swimming freely upstream to their spawning grounds.

Fyke Traps and Fish Highways

Catching Every Fish

That’s why returning adult salmon can’t complete their migration on their own.

Program biologists must capture every returning fish in special traps called fyke traps.

These large-diameter mesh cylinders are strategically placed in the river to intercept migrating salmon.

When adult spring-run Chinook are captured, biologists carefully handle each fish, often marking them with PIT tags or Floy tags and collecting genetic samples.

The Salmon Shuttle

Then comes the unusual part: the salmon get a ride.

Captured fish are loaded into specially designed transport tanks and trucked approximately 120 miles upstream to Reach 1 of the Restoration Area near Friant Dam.

This “trap-and-haul” operation ensures the salmon reach the cooler water and better habitat they need to survive the summer months before spawning in the fall.

Dr. Oliver “Towns” Burgess, the program’s lead fish biologist, explained the necessity: “Our fish need the cooler water and habitat of Reach 1 in order to hold over the summer before they spawn in the fall.”

Without this human intervention, the returning salmon simply couldn’t access suitable habitat due to the dams and diversions that remain in place.

The Breakthrough Year

Beyond All Expectations

The 2025 return exceeded everyone’s expectations.

When program manager Dr. Donald Portz announced the record-breaking 448 adult salmon, he emphasized what this means for the future: “The high return numbers clearly demonstrate that spring-run Chinook can survive and return to spawn in the San Joaquin River.

We look forward to a future where salmon will be able to swim unencumbered all the way to spawning grounds below Friant Dam.”

What the Numbers Mean

These 448 fish represent salmon that were released as juveniles in previous years, survived their ocean journey, and successfully navigated back to their birth river.

The nearly five-fold increase over the previous record of 93 fish in 2021 suggests the restoration program has reached a tipping point.

More returning adults mean more natural spawning, which produces more river-adapted juveniles, creating a positive feedback loop toward a self-sustaining population.

Halfway There

The program’s long-term goal calls for approximately 500 spawning pairs to establish a truly viable population.

With 448 adult salmon captured in 2025, the restoration effort has achieved nearly half that target.

Each successful spawning season adds genetic diversity and strengthens the population’s resilience.

What Success Looks Like

One of the Biggest Comeback Stories

The San Joaquin River restoration represents one of the most ambitious salmon recovery efforts in California history.

The program demonstrates that even rivers fundamentally altered by dams and diversions can support salmon populations again with proper management, water releases, and scientific monitoring.

The Work Isn’t Over

However, significant challenges remain.

The current trap-and-haul system is labor-intensive and expensive, requiring constant monitoring during the migration season and careful handling of every returning fish.

The ultimate vision involves removing or modifying barriers so salmon can migrate freely to spawning habitat below Friant Dam without human assistance.

The Water Wars Continue

Water availability continues to be a contentious issue.

California faces increasing pressure on its limited water resources from agricultural demands, urban growth, and climate change impacts.

The settlement agreement’s requirement for water releases means less water available for farms in the Friant Division service area.

Balancing these competing needs requires ongoing negotiation and adaptive management.

Lessons From a Dried River

Hope for Other Rivers

The San Joaquin River’s journey from ecological devastation to salmon recovery offers hope for other degraded waterways.

It shows that with political will, scientific expertise, stakeholder cooperation, and sustained funding, even seemingly impossible restoration goals can be achieved.

The 18-year lawsuit that led to the 2006 settlement demonstrated that legal action can drive environmental change when other avenues fail.

Why Diversity Matters

The restoration also highlights the importance of preserving genetic diversity.

By collecting fish from multiple Sacramento River populations rather than relying on a single source, biologists maximized the genetic toolkit available for San Joaquin River salmon to adapt to their new-old home.

This approach gives the restored population better odds of long-term survival in the face of changing environmental conditions.

Nothing Is Permanent

Want me to be honest?

The story of the San Joaquin River salmon reminds us that environmental damage from past development decisions isn’t necessarily permanent.

While we can’t simply undo the construction of Friant Dam or restore the river to pristine pre-1940s conditions, we can find ways to repair some of the damage and bring back lost species.

Looking Ahead

More Work to Do

The record-breaking 2025 salmon return represents a milestone, not a finish line.

Program biologists will continue monitoring returning adults, releasing juvenile salmon, and working to improve river habitat.

Plans include ongoing genetic sampling to track population health, acoustic tagging to study salmon movement and survival, and habitat improvements to support spawning and rearing.

The Hatchery Solution

A conservation hatchery near Friant Dam, delayed by construction troubles but now operational, can produce upwards of one million young spring-run Chinook annually.

This facility provides insurance against poor natural reproduction years and helps accelerate population growth.

The combination of hatchery-raised fish with naturally spawned juveniles creates a more resilient population.

Climate Change Questions

Climate change adds uncertainty to the restoration effort.

Warming water temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and more severe droughts threaten salmon throughout California.

Spring-run Chinook are particularly vulnerable because of their need for cold summer holding habitat.

The success of San Joaquin River restoration may depend on securing reliable cold-water releases even during dry years.

Symbols of Hope

Yet the 448 salmon that returned in 2025 prove that this species is a survivor.

After more than six decades of complete absence from the San Joaquin River, spring-run Chinook have demonstrated they can navigate the modern river system, survive in the Pacific Ocean, and find their way home.

That’s a remarkable testament to the persistence of wild salmon and the dedication of the people working to save them.

For Californians old enough to remember when the San Joaquin River flowed year-round and supported abundant fisheries, the restoration represents a partial recovery of what was lost.

For younger generations, it offers a glimpse of the river’s former glory and hope that humans can correct past mistakes.

The salmon swimming upstream today are more than fish – they’re symbols of resilience, restoration, and the possibility of renewal even in landscapes transformed by human development.